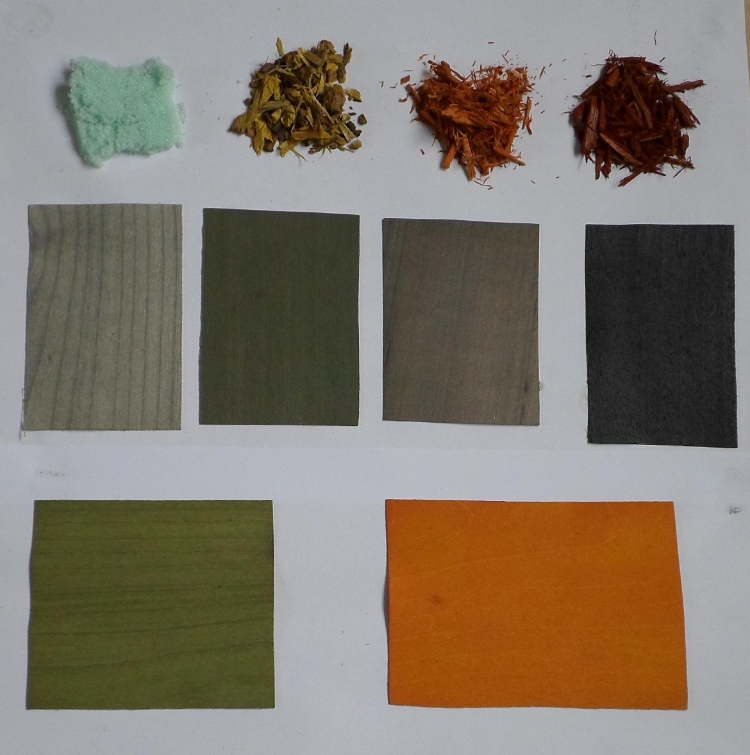

To minimise the weight of the head, wooden friction pegs has to be the obvious choice. The pegs that I have happen to be of a very dark coloured rosewood. The neck itself is made of Spanish cedar (cedrela).

Whilst I've retained the Torres head shape this particular guitar is not a copy of a Torres guitar. The soundboard bracing will be of my own design, a variation on fan bracing.

The back is now ready to receive the cedrela harmonic bars. The reinforcement of the back joints has been done with the use of a heavy weight 100% cotton rag paper. e to edit.

Whilst I've retained the Torres head shape this particular guitar is not a copy of a Torres guitar. The soundboard bracing will be of my own design, a variation on fan bracing.

The back is now ready to receive the cedrela harmonic bars. The reinforcement of the back joints has been done with the use of a heavy weight 100% cotton rag paper. e to edit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed